The Digital Free Trade Zone (DFTZ): Putting Malaysia’s SMEs onto the Digital Silk Road

By Tham Siew Yean, Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The DFTZ was launched in November 2017 in partnership with Jack Ma, Executive Chairman of the Alibaba Group.

- It aims to connect Malaysia’s SMEs globally through Alibaba-inspired electronic world trade platforms that are being established to support greater exchange between Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries.

- DFTZ challenges will include:

- Budgetary incentives to increase imports via e-commerce will intensify competitive pressures on domestic producers, although it can enhance transhipment.

- E-commerce platform usage will require an SME to have an export strategy, including an understanding of the regulatory regimes and documentation needed from home and importing countries.

- It remains to be seen if SMEs will sustain their membership on these platforms once government financial assistance ends, especially if the potential benefits do not materialize as expected, or quickly enough.

INTRODUCTION

China’s e-commerce giants have been quick in linking their global expansion to the aspired Digital Silk Road of China. In particular, Alibaba founder Jack Ma’s brain child, the electronic world trade platform (e-WTP), aims to connect small businesses globally through trade. This platform is associated with the Digital Silk Road since countries along the BRI are the most important regions for Alibaba and Jack Ma’s global expansion plans.

The establishment of the Digital Free Trade Zone (DFTZ) in Malaysia in partnership with Jack Ma, as the first e-WTP established outside China, is thus a step towards developing the Digital Silk Road. Currently, the only other eWTP that exists in the world is at Alibaba’s home province of Hangzhou. The DFTZ also aims to support Malaysia’s e-commerce dream as articulated in the country’s National E-commerce Strategic Roadmap, launched in 2016. In this Roadmap, the share of e-commerce in Malaysia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is targeted to increase to 6.4% by 2020 from 5% in 2012, by bringing in 80% of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) into the e-commerce world as well as by expanding market access through exports, investment and employment opportunities. Currently, it is reported that nine out of ten businesses in Malaysia are SMEs, of which 28% apparently have an online presence, with 15% using this involved in exports. The DFTZ specifically aims to facilitate SME export activities by providing platforms, e-fulfillment facilities and enhanced trade facilitation measures.

This article examines how the DFTZ will enhance SME export opportunities and the outstanding challenges that SMEs face in entering the export market through an ecommerce platform.

HELPING SMEs EXPORT

A traditional duty-free zone is a physical area into which goods can be imported duty free for further processing or for re-exporting. The DFTZ differs from this traditional zone in that it has a specific aim of digitizing trade to help SMEs function in international markets. The specific export target for SME is USD38 billion by 2025. If reached, this will make Malaysia Asia’s leading transhipment hub that same year. The DFTZ helps SMEs export by “connecting them to eMarketplaces, government agencies, cross border logistics providers, and cross border payment providers.”

E-commerce trade needs a whole range of services to support the speedy delivery of goods to customers. E-fulfilment, which encompasses the whole process from receiving a sales order to delivering the order swiftly to the customer, and trade facilitation, are therefore important components in this venture. The DFTZ aims to provide an eFulfilment hub, a satellite services hub and an eServices Platform. Its development is divided into two phases: the first is controlled by Pos Malaysia, which at a cost of RM60 million has been upgrading and renovating the former Low Cost Carrier Terminal (LCCT). This is already currently operational. The government budget for 2018, as announced in October 2017, includes an allocation of RM83.5 million for the development of this first phase. This mode of funding in the first phase of development differs from the traditional foreign direct investment (FDI) model, where the foreign technology partner usually provides some or all of the capital.

The satellite services hub aims to be a premier digital hub for global and local internet-related companies that are geared towards the Southeast Asian market. This includes end-to-end services as well as networking and knowledge-sharing.

In the second phase, Cainiao Network, the logistic arm of Alibaba, will partner Malaysia Airports in a green-field investment, which will be operational in 2020. Alibaba will reportedly host its regional eFulfilment hub at the Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) Aeropolis DFTZ Park. This Park will build on existing air freight infrastructure to include sea freight via Port Klang and railway cargo to Bukit Kayu Hitam, which will support a regional multimodal transhipment hub. The hub will subsequently be linked to Alibaba’s planned eWTP hubs in other countries.

Alibaba’s financial services will also be included eventually. Two of Malaysia’s financial services providers, Maybank and CIMB, have entered into an agreement with Ant Financial Services Group to establish the Alipay mobile wallet in Malaysia. Alibaba Cloud, the cloud computing arm of Alibaba group is also reportedly planning to establish a datacentre in Malaysia.

For the eServices platform, besides providing market access, integrated trade facilitation measures have reduced the cargo clearance time from six to three hours at the KLIA Air-Cargo Terminal 1 (KACT1). This is critical for the speedy delivery required in ecommerce transactions.

Currently, the two main e-commerce platforms available at the zone are Alibaba and Lazada, which has sold 83% of its equity stake to the former since 2017. According to Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC), there will be new e-commerce platforms joining from the second quarter of 2018 onwards. However, SMEs can also list in various e-commerce platforms outside the zone, including Alibaba and Lazada. In fact, Malaysia External Trade Development Corporation (MATRADE) has had an e-Trade programme with Alibaba since 2014, whereby approved SMEs are given an e-voucher worth RM1000, which is meant to defray half of the expenses for subscribing to Alibaba e-Trade Global Supplier Package. In January 2017, the e-Trade incentive for approved SMEs has been upgraded; it is no longer confined to Alibaba alone and the amount has also increased to RM5000, with RM2,500 for listing/subscribing purposes and another RM2,500 for e-commerce expenses associated with e-marketplaces. The main advantages of the zone for SMEs are therefore the eFulfilment hub, e-services, and trade facilitation measures that are or will be made available there. SMEs are also able to experience better exchange rates and lower shipping costs, based on customer feedback from Transcargo.

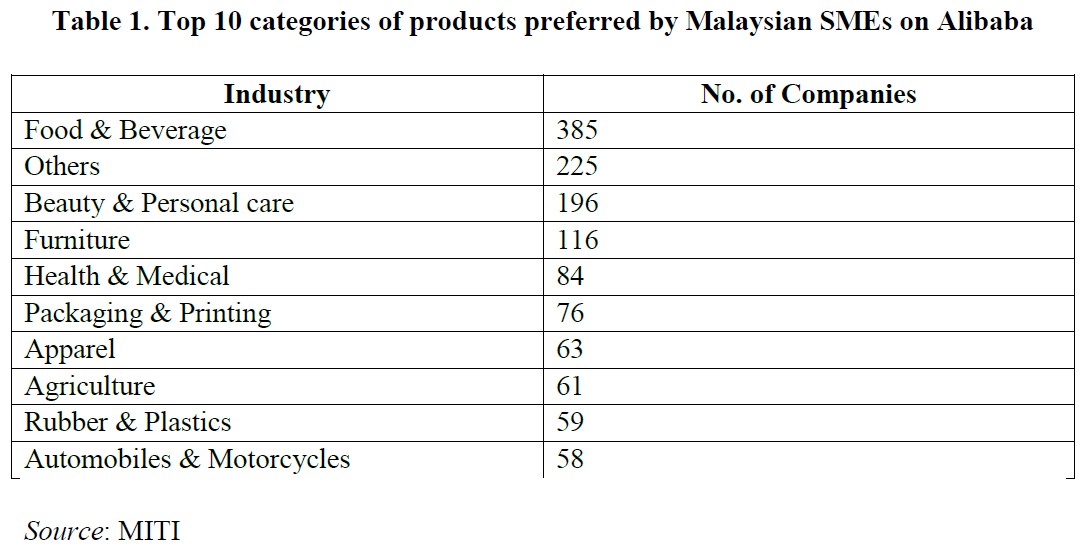

To date, about 2,072 export-ready Malaysian SMEs are on the ecommerce platforms in the DFTZ. Selangor, Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur and Melaka are the three states with the biggest number of SMEs participating in the DFTZ (69%), while the top three products preferred by Malaysian SMEs on Alibaba are food and beverage, others and beauty and personal care, which are mostly consumer products (Table 1).

OUTSTANDING E-COMMERCE EXPORTING CHALLENGES FOR SMEs

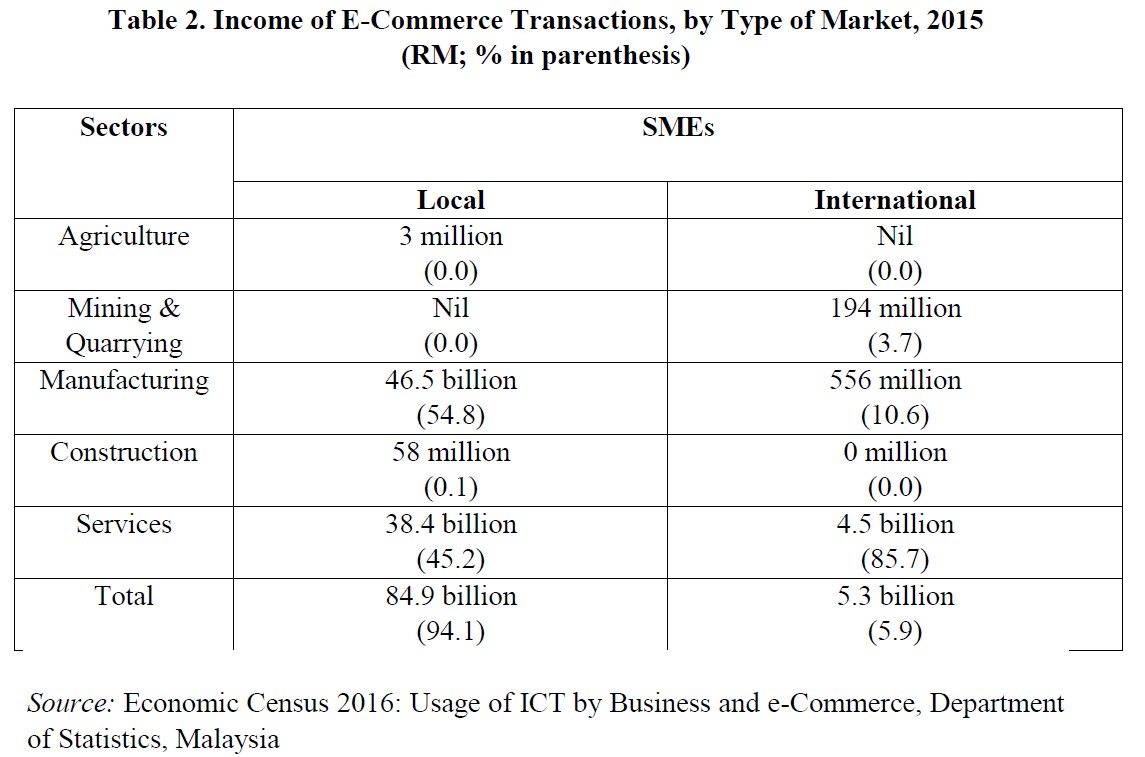

While for SMEs to join the e-commerce platform is a big step forward, using the platform to export is a bigger challenge for them. According to Malaysia’s Economic Census 2016, 43,460 SMEs are engaged in e-commerce, but only 5.9% of their income from ecommerce are derived from international transactions, which includes imports as well (Table 2). Moreover, the services sector is the largest contributor to international income from e-commerce transactions. Therefore, not many SMEs on ecommerce platforms are able to generate export revenues, and most of them focus on the domestic market. This is why the emphasis in the MITI website is on export-ready SMEs and not necessarily exporting SMEs.

The actual number of Malaysian SMEs that were already listed on Alibaba before the establishment of the DFTZ, is not known, but it appears that these have not necessarily been using the platform for exports, but for prestige. This is especially true of the Gold members. SMEs in general lack understanding of ecommerce, and lack competent personnel to conduct ecommerce activities and market goods and services. Therefore, SMEs that are passive exporters may consider being on an ecommerce platform as an end goal. Once there, they are happy to simply wait for buyers to discover them. Active or intentional exporters tend instead to seek out information on their competitors, the pricing of rival products and who the main customers are, from the same platform as well as other platforms. They will then reposition their product, using both product and price differentiation strategies to find buyers instead of waiting for buyers to find them. But, this requires SMEs to have an ecommerce export strategy, as well as personnel dedicated to this purpose. Furthermore, those who are not able to generate new or additional export revenues from their membership on the Alibaba and Lazada platform, may discontinue the association after a while.

Second, while the zone expedites the export documents needed, it will still require SMEs to obtain all the necessary documents by themselves. More importantly, it will also require them to obtain all the mandatory documents needed from the importing country as well. These may include legitimate concerns from the importing country such as sanitary and phytosanitary standards found in the World Trade Organization (WTO)’s Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS) Agreement. This is especially important in the case of certain consumables such as food and healthcare products, where SMEs will need to comply with local regulations for manufacturing consumables such as having a Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) certified facility that meets Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) standards as well as complying with the food safety requirements of the importing country. However, these non-tariff measures (NTMs) are sometimes used as importing barriers, be it intentionally or intentionally, and are called non-tariff barriers (NTBs). The fall in tariffs due to multilateral, regional and bilateral liberalization has been accompanied by a converse rise in NTBs, globally. Yet, SMEs in Malaysia and other countries continue to be ignorant about the relevant regulations, requirements and procedures when they export to other countries. These barriers will continue to restrict SMEs in penetrating the export market, even with the full availability of the promised infrastructure in the zone. Hence, they will need to learn how to comply with rules and regulations, as is the case with offline exports.

Budget 2018 also announced that goods bought online will be exempted from tax in the DFTZ as long as they are worth RM800 (about USD 203) and below — a higher threshold than the earlier de minimis value (RM500). This encourages import, be it for personal consumption or for re-export, although goods will have to pay the Goods and Services (GST) tax if and when they leave the zone. In contrast, China’s de minimis is USD8, which discourages imports of higher value. This, together with the declining comparative advantage of Malaysia’s exports of consumer goods to China, inevitably implies that competition, especially from China, will further intensify with the establishment of the DFTZ. Although the transhipment of goods may increase, this may come at the cost of some SME producers exiting the industry, including some SME retailers and local SME third party ecommerce providers, as they will face stiff competition from the DFTZ.

CONCLUSION

The establishment of the DFTZ is hailed as a milestone in Malaysia’s national digital economy agenda. It is currently tapping on Alibaba’s system and technology for facilitating ecommerce development in the country. The cost of all these developments is currently funded by the Federal government’s budget allocation and Pos Malaysia.

The wish to increase the export contribution of SMEs from the current 18.6% to 23% by 2020, makes it necessarily for the government to use ecommerce for that purpose. Yet getting on board the ecommerce train does not necessarily increase exports. Changes in the SMEs’ ways of doing business will be needed. SMEs will need to embrace exporting activities with a proper e-commerce export strategy, including compliance with the rules and regulatory requirements of targeted export markets. In particular, the DFTZ also eases entry of imports as the change in the de minimis threshold favours imports over exports. This increases competitive threats to local SMEs, which are already facing declining comparative advantages vis-a-vis China, especially in consumer goods.

The establishment of the DFTZ will therefore require SMEs to formulate new business strategies that will help them survive in the domestic market and penetrate the export market.

This commentary first appeared in ISEAS Perspectives 2018 no 17. Read the original article here.